|

July 12, 2014

Raoul Wallenberg and the art of the impossible

Seventy years ago this month, as World War II raged, American and Swedish officials came to the aid of the last surviving Jewish community in Europe. The decision to send active assistance to the besieged Jews of Hungary was made very late. US president Franklin Roosevelt had ordered the creation of the War Refugee Board only in January 1944. But once it was established, its representatives moved quickly to reach out to neutral countries like Sweden to find ways to render urgently needed help.

My uncle, Raoul Wallenberg, was ready to answer the call to action. And it is thanks to this readiness to join forces against evil, across national boundaries and against ordinary thinking, that tens of thousands of Budapest’s Jews were saved.

As we celebrate this success, I cannot help but reflect over the years of pain and sorrow that ensued for my grandparents and Raoul’s siblings when he himself became a victim in January 1945, after advancing Soviet troops arrested him, in spite of his diplomatic status, and he disappeared into the Soviet Union.

From the day he was born, Raoul had been the light in his mother’s and grandmother’s lives, both of whom had been widowed shortly before his birth. The young boy represented a beacon of hope to cling to amid the two women’s intense grief.

In 1944, Raoul was sent on a dangerous mission without any adequate protection, formally representing his country and, indirectly, also the US. Yet, once he disappeared, there was no authoritative voice that stood up for him in the way that he had done for others.

Instead, what followed was a deafening silence that left Raoul’s parents reeling and desperate for answers. All they found were Swedish officials who averted their eyes and turned their backs when they entered a room. Raoul’s influential relatives – the Wallenberg banking family – showed no outward sign of bother over his loss nor did they appear to be interested in determining ways in which he could possibly be saved.

My grandmother was a very strong woman, but the sorrow and nagging uncertainty over the fate of her son, as well as her inability to rally effective help, slowly wore her and my grandfather out. Raoul’s siblings, his sister Nina Lagergren and my father, Guy von Dardel, had joined their parents’ fight from the start. They never let up in this commitment.

My father essentially took on two full time jobs. Aside from raising a family, he somehow found a way to divide his time between the rigid demands of a career as an experimental physicist at CERN (Switzerland) and the all-consuming search for his brother.

In this search my father was as uncompromising as Raoul was in his fight for the Jews of Budapest. Even as his health declined in later years, his fighting spirit remained undaunted.

In 1984, in a daring move, he sued the Soviet Union in a US court. My father won in the first round, and the presiding judge ordered the Soviet government to immediately provide information about Raoul’s fate and to pay $39 million in restitution. The verdict was later set aside, however, over US government fears that its execution would negatively impact US-Soviet relations.

Since Raoul was nominally a Swedish citizen, the US, unfortunately, chose to stay largely in the background of the search for clues to his fate. It is perhaps worth noting that it took a full six years after Raoul’s disappearance before Sweden formally approached the US government for help. It is also a fact that over the next six decades Swedish officials repeatedly rejected American offers of assistance in the case.

Regrettably, when my grandmother, in utter desperation, turned to secretary of state Henry Kissinger in 1973, he declined to take any action, apparently angered over the leftist, anti-American policies of the Olaf Palme government.

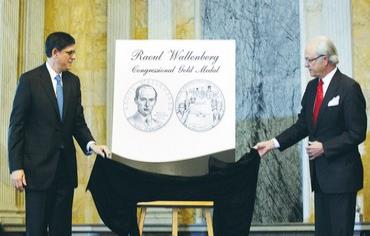

Eight years later, president Ronald Reagan made Raoul an honorary citizen of the US – a remarkable turn of events that my grandparents did not live to see. They ended their lives, exhausted and dispirited, in 1979.

The moment the Soviet Union opened up in 1989, my father was there to lead the quest for his brother, together with an international team of researchers. He sought and received permission to conduct the first ever on-site investigation of Vladimir Prison, Russia’s most important isolation facility. Many witnesses had reported hearing of Raoul’s presence there after 1947.

A 10-year investigation of an official Swedish-Russian Working Group that followed yielded many important results but could not answer the central questions in Raoul’s case: Why did Stalin decide to arrest him and why was he never released? And what happened to Raoul in the crucial summer of 1947, when his trail breaks off in Lubyanka Prison? In 2001, my father’s application for Raoul’s formal rehabilitation was granted [in Moscow.] Since then, researchers have continued our family’s search and have kept up a constructive dialogue with Russian authorities. Unfortunately, as was the case during the 1990s, Russian officials have consistently refused access to key documentation, especially highly relevant files kept in the archives of Russia’s intelligence and security services, as well as collections that could reveal much needed information about how the Soviet leadership assessed Raoul’s case through the years.

In 2009, important evidence emerged that as far back as 1991, essential documentation in the Wallenberg case had not been shared with researchers or our family. This material shows that Raoul may have been held as a numbered prisoner – “Prisoner No. 7” – in Lubyanka Prison, on July 23, 1947, six days after the official Soviet and later Russian version of his alleged death (on July 17, 1947).

To our great disappointment, Swedish officials have seemingly tolerated these deliberate omissions or at least have not vigorously insisted that these missteps are fully remedied. Numerous other important questions have remained unanswered for decades, including questions about one or more highly secret Swedish prisoners apparently incarcerated in Vladimir prison some time in the years 1947-1972.

The censoring and intentional withholding of documentation is a serious matter because it may be indicative of a broader pattern or policy. Russian officials have repeatedly stressed that they face no limitations to presenting the complete facts in the Wallenberg case. The recent revelations, however, raise doubts that this is indeed so.

We have often wondered why there has not been a more serious effort to press the Russian government for access to highly relevant collections. It is quite obvious that if researchers were empowered to do their jobs, important progress regarding the core questions in the Wallenberg inquiry could almost certainly be made.

For us, other question marks persist: What exactly have Russian and Swedish decision makers known about Raoul’s fate and when did they know it? And do they possess knowledge today they have not shared with the public? Frankly speaking, it has been quite disheartening to see that official representatives – those who have the power to act – have been seemingly content not to explore all options available to them.

When our family turned to President Barack Obama in 2013, to ask for his assistance in urging Russian President Vladimir Putin to provide direct and uncensored access to key documentation, we were told once again that “the time was not right” for confronting Russia.

And so we have gathered once again in Washington, DC, this week, to honor Raoul’s achievements and the proof he represents that the good in us can overcome any evil, no matter how vicious, if we put our hearts and minds to it.

Raoul understood one fundamental thing very well – that “human rights” is not just simply a general term. To borrow a phrase from the US religion scholar Cornel West, meaningful assistance to human beings in need has to be hands-on, it has to be “tactile.” It cannot ever remain merely theoretical or cerebral.

In the hell that was Budapest in 1944, against seemingly insurmountable odds, Raoul found a way to be effective.

He was a true visionary, who did not take no for an answer.

He was a devoted practitioner of what the playwright and former president of the Czech Republic Václav Havel has so aptly called “the Art of the Impossible.”

Have felt that even though in today’s complex world the choice between “lesser” evils often seems to be our only option, we should be careful not to forget to strive for the “ideal” outcome. We, the citizens of democratic societies, he argued, have to maintain a constant vigil to stay true to our declared humanistic and democratic principles.

Raoul’s mission to Budapest was precisely that: true humanistic philosophy in action. He left behind his comfortable life in Sweden, and he threw himself into the task of making this very concept a reality. For that, he not only richly deserves the honors that have been showered upon him, but he also deserves something more: He deserves justice.

Raw courage, both physical and moral, is Raoul’s true legacy. His work in Hungary graphically illustrates that if we want to effect change, if we want to oppose tyranny, we have to raise ourselves up – literally – and fight against it.

Next January, 70 years will have passed since he left, on a cold January morning, to meet with Soviet representatives in order to ensure that the Jewish safe houses he and his colleagues had established would be respected and protected.

For our family, the fight continues. We will not and cannot be satisfied until we have full answers. But we also can no longer carry the enormous burden of the investigation alone. My hope is that the world will stand up, just as Raoul once did, with so much courage and so much heart. It would be a fitting tribute to him and to the many millions of victims of totalitarian regimes the world over who have suffered and continue to suffer as a result of our silence.

The Jerusalem Post

|